Newark schools have dealt with lead-tainted water for decades

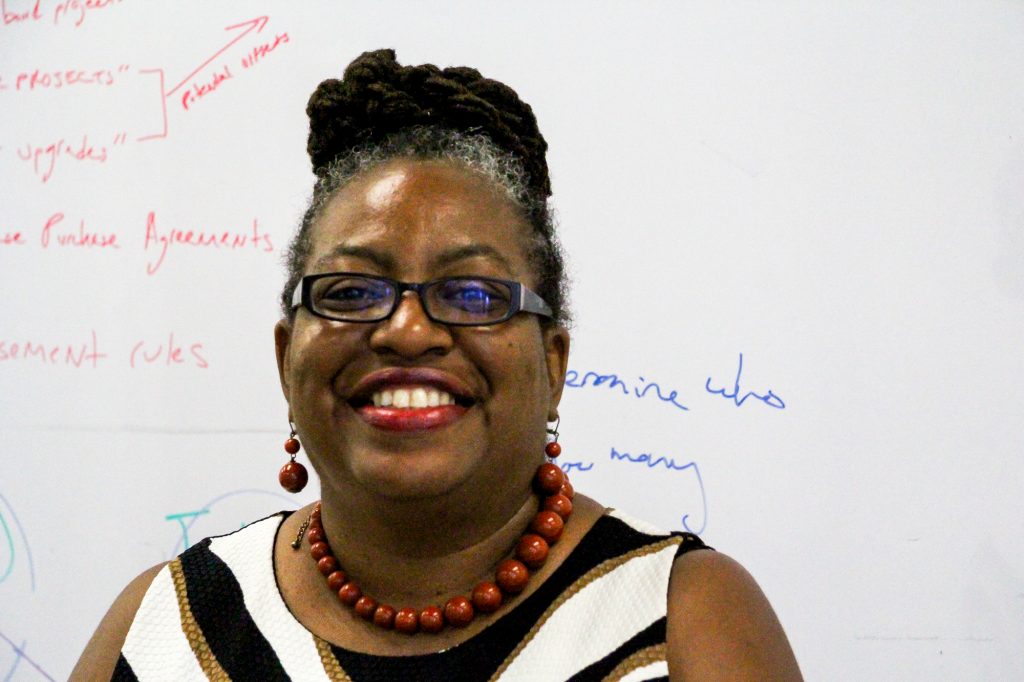

Yolanda Johnson, a parent at George Washington Carver Elementary School in Newark, New Jersey, said she will advise her 13-year-old daughter to avoid drinking from fountains when they’re turned back on. Johnson buys four cases of water bottles a month, one of which she gives to her daughter. (Photo by Fraser Allan Best/News21)

NEWARK, N.J. – When Kim Gaddy’s godson got lead poisoning from ingesting paint chips, she said he suffered irreversible brain damage that affected his memory and academic performance. That made Gaddy, then a member of the school board in Newark, New Jersey, turn her attention toward the place where children spend most of their days.

“I said, ‘How do we know it’s not in school?’” Gaddy said. “That’s when I was first elected as a board member. They did an investigation and found out that there was lead in the drinking water.”

That was in 1994. More than 20 years later, lead continues to contaminate Newark Public Schools’ water. And Gaddy continues to fight for clean drinking water as a parent and school board member.

About half of Newark schools tested high for lead in April 2016, according to test results released by the school district. The district shut off fountains and installed lead-reduction filters, even though they had done the same thing in 1994 and 2002.

Along with publicizing its 2016 test results, the district released annual water testing data from the past six years. It revealed that about 12 percent of 4,137 samples taken since 2010 exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s limit for lead.

While the news shocked the rest of the country, it was all too familiar for Newark residents.

“If you talk to people in Newark, they’ll say to you, ‘I remember being tested for lead when I was younger,’” said Valerie Wilson, school business administrator at Newark public schools. “Newark as a city has had a lead management program for kids for the longest that anybody can remember.”

Kim Gaddy has advocated for clean drinking water as a parent and school board member at Newark Public schools since the 1990s. (Photo by Fraser Allan Best/News21)

Gaddy said frequent changes in school leadership led to a lack of oversight when it came to lead contamination. Newark became a state-controlled school district in 1995, and it has gone through numerous superintendents since then. Things once prioritized by previous administrations, such as lead testing, lost the attention of new leadership, Gaddy said.

“People are just not educated about the issue, and they think it’s OK because somebody else is going to take care of it,” Gaddy said.

Newark’s lead problem persisted until 2014, when officials discovered lead-tainted water in Flint, Michigan, and it sparked a massive public health crisis.

“If there wasn’t a Flint, everything would’ve gone on as usual,” said Yolanda Johnson, a parent at George Washington Carver Elementary School in Newark. “When Flint, Michigan, came out, everybody started testing.”

Newark is a heavily industrialized city filled with century-old buildings. Toxic pollutants contaminate the city’s air, water and land, and there’s little funding available to clean it all up.

Lead experts and education advocates said it’s too expensive to replace old pipes, so lead will remain a widespread and persistent problem at Newark schools.

“There’s a lot that goes into the remediation process, and the biggest obstacles are money and time,” said Maria Lopez-Nuñez, who works with the Ironbound Community Corporation in Newark. “I think in a district like Newark that has to pick and choose what it’s going to work on, that becomes complicated when so many schools just need overall replacement.”

Valerie Wilson, school business administrator for Newark Public Schools, talks about the school district’s ongoing plan for lead remediation. (Photo by Fraser Allan Best/News21)

Until the school district can consider renovating old buildings, it will have to remediate within its means. In April 2016, the district vowed to install filters that automatically shut off when they need replacement.

Gaddy said she hopes such measures will prevent further lead contamination since these filters rely more on technology and less on human error.

“I’m looking forward to better results,” she said. “And from everything I’ve heard in the meetings, I’m confident that this time, they’re going to get it right.”

To see the full News21 report on “Troubled Water,” go to troubledwater.news21.com on Aug. 14.