Federal agencies have a duty to provide services for Native Americans as a result of treaties. This relationship means that when tribes do get funding, they often don’t control it. For example, the Navajo Nation’s $1 billion settlement to assist in cleanup of old uranium mines was awarded to the EPA, not the Navajo. “Reservations themselves should be entitled to that money directly,” Andreini said. In some cases, however, they don’t have the capacity to implement their goals.

Even knowing where to turn presents a challenge. The EPA regulates water on tribal lands, and its representatives’ offices are often in a different state. Within the Apsaalooke tribe’s designated EPA region, two dozen tribes share three or four managers.

“Regular access and dialogue between effective decision-makers – those are limited,” said Robinson, the public health researcher. “Then those agencies spend a lot of money on staff and travel and not building capacity of tribes to do work.”

While the EPA enforces national water standards on Native American lands, many other agencies oversee the implementation and maintenance of infrastructure, such as Indian Health Services, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the U.S. Geological Survey, the Department of Energy and in some cases state agencies – complicating the delivery of water services. It also makes it easier to point fingers and shirk responsibility, Andreini said.

Andreini said he often hears government officials and politicians say they don't understand how tribal governance and systems work, challenging their ability to come up with solutions.

Fawn Sharp, vice president of the National Congress of American Indians, said tribes have limited power to raise taxes, which is why they have to secure money from many sources. “The end product is what you see, programs where it may take up to 14 sources of funding to make happen,” she said.

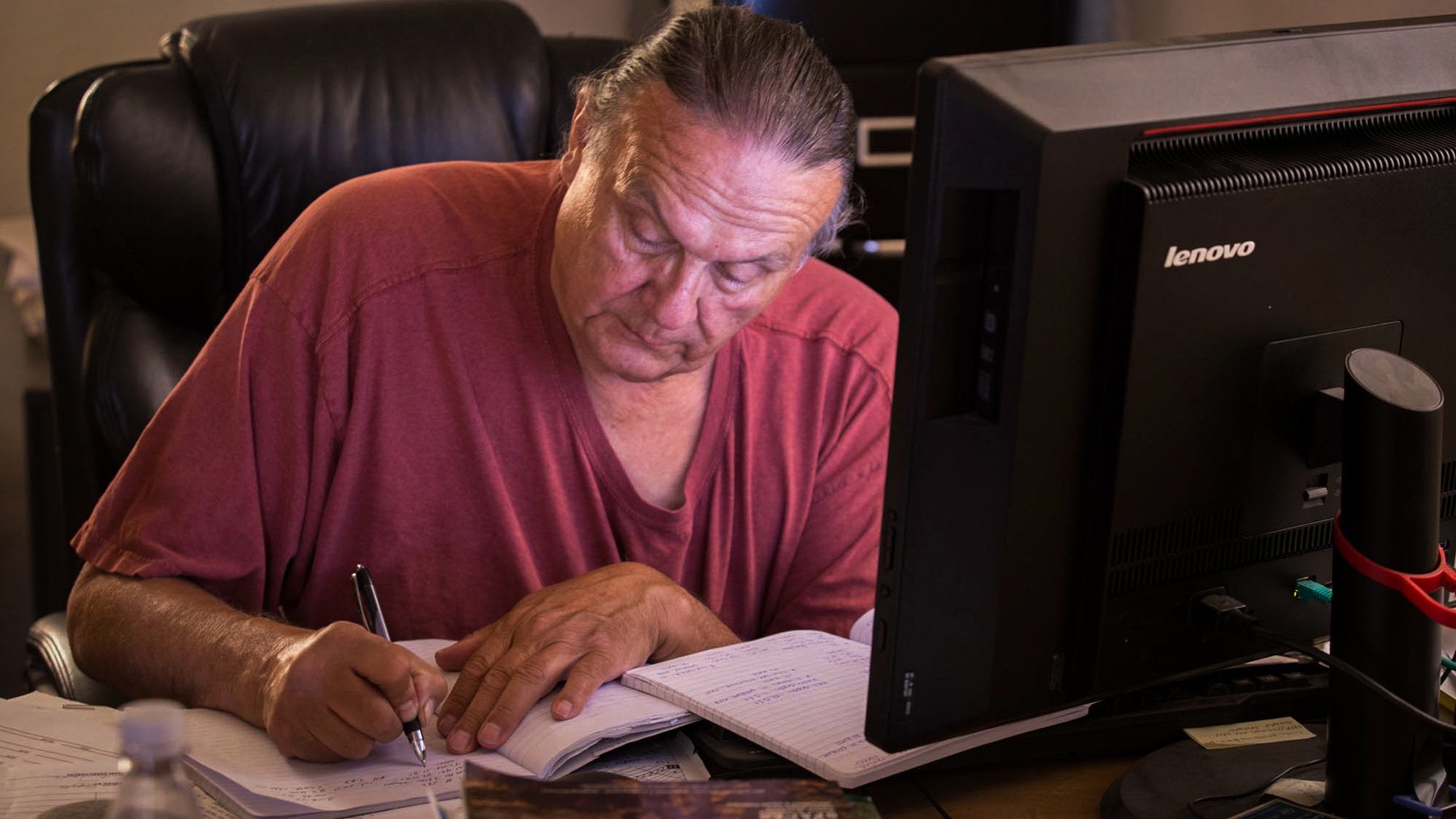

That’s how many loans and grants it took for Doyle, a member of the Apsaalooke wastewater authority, to raise the $20 million to fix the leaking wastewater and failing pipes on the Crow Reservation.

Gerlak, the water policy scholar, said that newer models of complex financing that have come as a result of government agency cuts – such as loans, bonds and public-private partnerships – don’t always work for poor, disenfranchised communities.